Peter Rose

I’m pleased to have an opportunity to speak at the launch of this welcome new publication from Monash University Publishing.

Australian Book Review is a partner of Monash University through its Faculty of Arts. It’s a partnership that has grown since its creation in 2016 – and one we take seriously – through publication of Monash staff and students (some included in this anthology), through talks and publishing masterclasses, and through an active internship program. So we’re attuned to what’s going on at Monash, and we follow publications from its press with interest.

I understand this is the seventeenth edition of Verge. That’s an impressive history for any publication. So Verge has been verging, as it were, for almost two decades. I’m all for verging and indeed divergence. Anything that showcases emerging and established artists is to be welcomed. Verge does this well. It’s somewhat unusual among publications of this type because of its integration of work by current students and of those with established publication records. That’s a journal and an anthology’s responsibility – to spotlight the established, the assured, but also to nurture the young, the emerging, the innovators.

This policy of integration a good thing. We know what a fillip it is for young writers to appear in journals and compilations along with writers they admire.

My poetry first appeared in 1985 in a magazine called Scripsi – conceived just around the corner at Ormond College. What a buzz it was to see my callow poems appearing alongside works by laurelled poets such as John Ashbery, Peter Porter, Laurie Duggan, August Kleinzahler (they were nearly all blokes in those days).

That buzz never really goes away whenever work appears in print, however many poems or books one has published. Last week I received my copy of the new Meanjin, which carries another of my Catullan satires. I felt the same kind of frisson I experienced back in 1985. I don’t think I’m alone. Publication in permanent print form has a unique cachet.

There’s a sense of connection – gratification that the work formerly so private, so vested, so precious yet so ambiguous and elusive, is finally making its own way, beyond one’s own fretting and possessiveness. Text transcends the author, as it should.

I indulge in this slightly confessional mode merely to highlight what I see as the primary role of this kind of publication – which is one of connection and inclusiveness. Authors are not necessarily very trusting or inclusive people. Publication may be the auction of the mind (as Emily Dickinson wrote) but it also bridges the gap between author and reader.

How vital these publications are in 2023 – and how laudable it is that Monash University Publishing goes on investing in and promulgating this ensemble publishing.

Works of this kind – like journals and magazines – are indispensable components of what we are sometimes encouraged to think of as the literary ecology. Right now – during the age of Covid and at a time when recession threatens – journals, like artists in general, are doing it particularly tough. We know how grim the past three years have been for writers and artists. The data about incomes and security are bleak – shaming too for such a wealthy and educated country.

This makes the federal government’s newly released national cultural policy even more critical. All eyes are on Revive, and I am sure we wish the federal government and the Australia Council as it seeks to shape the new Writers Australia. Much will depend on how much money is restored to the pitifully underfunded federal arts budget – one that actively discriminates against literature. I don’t need to remind this audience that Australia Council of literature has been bogged at $5 million dollars for three decades. Three decades! At the risk sounding like Gilbert and Sullivan – it would be hilarious if it weren’t so deleterious.

Now, government has a chance to redress this historical neglect. And here – to my mind – not just publishers and gatekeepers (if that’s what we are) – we all have an opportunity and a responsibility to lobby government and the Australia Council to ensure that past neglect of literature is overturned and that the journals and publishers that nurture young writers and pay them fairly are supported.

But we’re here of course to talk about Verge – not governments and financial exigencies.

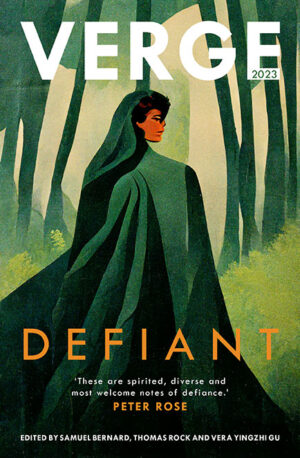

Verge is edited by Samuel Bernard, Thomas Rock and Vera Yingzhi Gu. In their introduction they note:

Defiance is too often associated with rebellion, insurrection or revolution, though the act is exquisitely heterogeneous. For Verge’s 2023 issue, we challenged writers to ponder this timely and universal concept.

The results are promisingly multifarious. The contributors – all 31 of them – write about forms of resistance and defiance – from the domestic to the planetary. There are stories and poems about domestic challenges, gender issues, the perils of identity, and what Cameron Semmens in his poem ‘Exiting the Forest’ calls ‘the crawling fear of environmental apocalypse’.

But defiance takes many forms – some active, political – others moral, instinctual, epistemological.

While I have written in other forms (fiction, memoir, criticism), I have devoted much of the past forty years to poetry – without ever really stopping to consider why I actually write the stuff; what it is that motivates me; what it is I am trying to effect. Here, I am rather like Thom Gunn, who once wrote: ‘I am interested in individual poems, not in poetics.’

Only lately have I begun to reflect on the properties and dispensations of poetry.

Each poem, each donnée, each poetic state surely represents a kind of refusal – a retreat from conventional ways of perceiving life, family, nature, relationships, society, mortality.

What are we doing as poets when we succumb to a poem but seeking unique metaphors for reality – ones never shared, never conceived before, too weird for public circulation.

‘Étonné-moi’, the impresario Diaghilev famously exhorted Jean Cocteau – and that was a good century ago. Surely it’s the artist’s duty to astonish us – not to echo, not to reinforce, not to concur. There is far too much yea-saying in this country. This is such a conformist age, when politicians and admen and social media zealots and corporate masters exhort us to think and act in certain ways, not to rock the boat, to express ourselves along certain lines. What a betrayal of intellectual freedom and the artistic life.

I am in total agreement with W.H. Auden, who declared: ‘Alienation from the Collective is always a duty.’

Albert Camus once said, ‘The real passion of the twentieth century is servitude’. Sometimes I fear that even worse forms of subservience and intimidation are loose in the twenty-first century.

Another quote (I am very quotatious tonight!) – from Wallace Stevens, one of the great poets of the twentieth century. It comes from his collection of epigrams called Adagia – indispensable reading for any poet: ‘The imagination wishes to be indulged.’

So let’s indulge it – and celebrate it.

Angela Jones has a poem in Verge and it contains a wonderful refrain – ‘Oh, the places you won’t go’, she repeats. I suppose my small point is that there are no places where writers shouldn’t venture – however private, subversive, imaginary.

I will end with a quote from James Baldwin – boldest of social critics – most eloquent of twentieth-century American writers. He wrote:

‘All art is a kind of confession, more or less oblique. All artists, if they are to survive, are forced, at last, to tell the whole story, to vomit the anguish up.’

Telling the whole story, yes, vomiting it up – not just half of it either, and certainly not the savoury or orthodox bits – is a writers’ responsibility. It’s the promise of such that admirable publications like Verge enable writers and thus readers to explore.

I wish it every success, and I congratulate everyone associated with this edition.

Readings, Carlton, 21 March 2023

-

Verge 2023

Samuel Bernard, Thomas Rock and Vera Yingzhi Gu

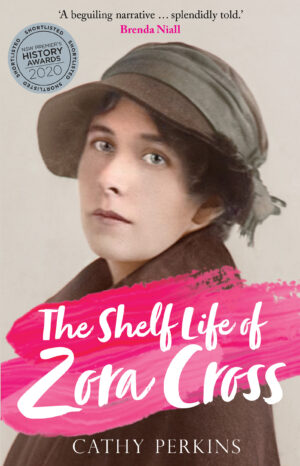

Again I felt an immediacy, as if I was quietly there in the room too, watching Zora concentrating at her typewriter, older now, but writing with the same intensity of focus and dedication that Perkins presents vividly as Zora’s mode of living and working.

Again I felt an immediacy, as if I was quietly there in the room too, watching Zora concentrating at her typewriter, older now, but writing with the same intensity of focus and dedication that Perkins presents vividly as Zora’s mode of living and working.

We are delighted to announce various staff changes at

We are delighted to announce various staff changes at