With great sadness we share that Graeme Turner AO FAHA FQA, Emeritus Professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Queensland has died. Graeme published thirty books and his work has been translated into eleven languages.

He was president of the Academy of the Humanities, a former Federation Fellow, and the only humanities scholar to have served two successive terms as a member of the Prime Minister’s Science, Engineering and Innovation Council. Graeme had extensive engagement with higher education policy, research assessment and commentary on the sector, including prominent roles with the Australian Research Council, the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy, and the Learned Academies.

He co-authored the landmark 2014 study of the state of the humanities, creative arts and social sciences disciplines in Australia, Mapping HASS.

Graeme’s AO was awarded in 2019 in recognition of his pioneering work in cultural studies and his contribution to higher education.

Greg Bain, Curator of the In the National Interest series, describes Graeme’s passing as ‘a huge loss but a giant legacy to humanities scholarship – he was a valued and supportive colleague to so many. He was a warm and genuine soul. A passionate and superb communicator, especially through his books – and a privilege to publish.

He will be sorely missed.’

Graeme’s recent book Broken: Universities, Politics and the Public Good – in the In the National Interest series – was a bestseller. His energy in bringing the discussion to a wider readership was unflagging – he was an energetic, thoughtful, generous and gracious author and colleague.

Monash University Publishing sends condolences to Graeme’s family, friends and colleagues.

(*with thanks to the Australian Academy of the Humanities for this information)

As the holiday season fast approaches, there’s no better way to celebrate than by gifting – either to yourself or your loved ones – captivating reads. Consider a range from our Top Ten books this year. If you buy two or more titles from this selection, we’ll give you 25% off as a little sweet treat for your stocking, plus we’ll throw in free shipping within Australia. Just use this code: 2025TOPTEN. (Minimum spend $45.00)

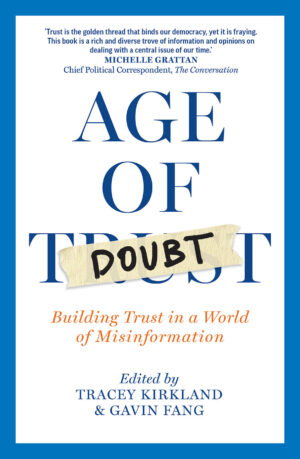

Delve into a hidden part of Australian history with Diana Thorp’s Code of Silence, discover the art of diplomacy with The Curious Diplomat by Lachlan Strahan, or become an expert on ’80s music with Tony Wellington’s Mixtapes and MTV. Be amazed at the uphill battles and prejudice Sarah Arachchi faced in Brown. Female. Doctor., reflect on the past 50 years with Dennis Altman’s Righting My World, or take a closer look at art crime with Unseen by Penelope Jackson. Peer into the lives of some of Australia’s best contemporary artists with Quentin Sprague’s What Artists See, marvel at the story of the post-war artist community on the Greek island of Hydra in Half the Perfect World, confront the possibility of technoscience conquering both nature and humanity with Richard King’s Brave New Wild, or learn how to build trust in a world of misinformation with Age of Doubt.

Order by Friday 12 December to make sure they arrive in time, and we’ll even wrap them up for you.

At the checkout page, please let us know in the ‘order notes’ section if you’d like all your books wrapped together, individually, or in specific bundles.

Don’t forget to add the discount code to the cart at checkout.

-

Code of Silence

Diana Thorp

-

The Curious Diplomat

Lachlan Strahan

-

Brave New Wild

Richard King

-

Unseen

Penelope Jackson

-

What Artists See

Quentin Sprague

9/10/2025

Thanks for inviting me to launch this timely book. Schizophrenia is not a sexy subject. But we need to know about it as it continues to disrupt the lives of so many people. It remains out of sight and mind until there is a PR disaster, and the media whips up a moral panic in an already primed community which is pulsating with stigma.

When I was diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1976, it was a death sentence with a dire prognosis. I was told I was on a pathway to irretrievable madness from which I would not recover. My future was set to be a mire of madness with no hope, purpose or meaning, a downwardly spiralling trajectory to poverty, unemployment, no friends, and life on an invalid pension, and a raft of unfulfilled dreams. The sense of failure was profound. The shame cut into my psyche like a scythe. This shame came from the stigma associated with the diagnosis, with that phonetically charged word which carries years of accumulated baggage created by an uninformed and sometimes hostile media, or from Hollywood who portrayed us as mass murderers or mad geniuses and not ordinary folks like me. Popular cultural representations, and these days, social media, compound the perceptions and understanding of schizophrenia.

With the stigma and shame around schizophrenia, came also a profound silence, a reluctance to disclose my diagnosis, to expose my feelings of failure. There was no conversation about anything to do with it. Even when I went to the library to find books on schizophrenia, it was textbooks which informed me with the pessimistic medical model and dire clinical prognostications. It was difficult to find books which gave an overview from multiple viewpoints of what I had been saddled with, to find information that gave me hope. The narrow clinical view was limited and gave little joy.

This is why books like Living with Schizophrenia are so important. Offering multiple viewpoints from those who live with schizophrenia, those who care, clinicians, allied health professionals, first nations advocates, and consumer advocates, allows for a more positive sense that there is hope, though it is a qualified hope dependent on so many variables swirling around the concept and experience of schizophrenia.

Given all the misinformation and stigma associated with schizophrenia, we have to have a serious and reflective conversation which is not tainted by media hysteria, pseudo-science, stigmatised attitudes or Hollywood mythology. A book such as this starts that conversation. I admit I found the book challenging on many fronts. I confess, I found the carers stories hard to read, because I was challenged by their frustration, pain, grief, loss and doubts about their roles in caring for a son or daughter. It sent me into a spiral of profound guilt, knowing the difficulties I have created in the past for my friends/carers. I haven’t always acted appropriately, and I have created my own realm of havoc. Reading the stories reminded me of things I would rather forget. Sometimes it’s hard not to see things through a personal fog.

But there can be growth from this fraught relationship as demonstrated by many of the carers who show a collective hard-won wisdom. The myriad emotions, the mistakes made, the deafening silence from family and friends, the withdrawal of one’s network, the inexplicable anger, the strain on family relationships and marriages, the loss of friends, who to blame, being ignored by clinicians, all these come into play when mental illness enters a family, and a son or daughter suddenly withdraws and becomes a stranger. Learning to live with uncertainty and with little or no support, and often being blamed for having caused the schizophrenia in their child, forces carers to find a resilience many cannot comprehend. Having to navigate a murky, and often unhelpful, mental health system, is frustrating and disempowering. Helen, Mother of Kevin, in describing where carers sit in the mental health system sadly said we family members are the lepers in the system. And people in the mental health services have scant knowledge of family trauma. The stories of the families are heart-wrenching. Lydia, mother of Kosta, says: We became a very quiet family, with no more dinner parties and though all our friends knew, they either continued to see me or cut me off completely. Reading these stories is disturbing, but they also show the courage, the admissions of making mistakes and the wisdom gained, is enlightening. The desperation they hold for their children to not be mentally ill, to not be suffering the dire side effects of their medication, to not be socially isolated, stings, but the acceptance reached by many carers of what is, is instructive. In all of this, there is no choice for anyone in a situation which tests everyone’s patience and resilience and self-acceptance, listening abilities and strategies for getting through the challenging times.

The counterpoint narratives to the carers come from the sons and daughters offering a window into the psychotic experience; to what living day to day looks like. While the 10 people share a diagnosis, they each experience it in their own unique way. Some have support, others don’t. Some are able to reflect on their condition while others are still grappling to hold onto reality. There is a lot of sadness and a sense of loss in these stories.

Family dynamics and loyalties are tested. Perry, imbued with the grand sweep of Greek mythology, sees his family through an intriguing but troubling lens: My relationship with my family was weird because one moment I’d love them and then the next day the voices would say: ‘Your brother is Poseidon, flatten him. He possesses you. Your father Hermes is protecting you. Love him. Now he is the devil – hate him. Your mother is trying to poison you. She’s a good cook – love her or hate her. Your brother is the Holy Ghost. He possesses you. Kill him. Perry goes on to say: I thought I was the son of Zeus and that while he slept, Olympus wanted to reconquer the world…that I was immortal and when I died my heartbeat would kill every heartbeat on the planet. The mind at play, creating a vast creative canvass of a complex cosmology, is quite extraordinary.

The sense of loss is apparent in some of the stories. Lionel laments that he used to be brand new but I’m not anymore. And getting sick is like being a prisoner in oneself. It feels like you’re tied down. Guiseppi doesn’t meet many people. I go to the hotel, and I sit there drinking a beer on my own. It’s like I am disconnected from everything, completely disconnected. I know I have been a hard person to get along with. I’ve been so sensitive, it’s difficult for people to be around me.

The ability of the mind to construct an alternative reality never ceases to amaze me. The rawness of some of these stories show the psychotic mind weaving its creative dark magic. And how it can place a barrier between the person and the outside world. John contends, it’s rough when you think you’ve saved the world and saved yourself and get locked up in F12 – which is the lock-up ward at Mont Park Hospital. It’s criminal when…your only crime is saving the world. His worst experience of all was being in hospital and thinking I was failing my mission for God. I didn’t hear voices, only my conscience. And people saying, ‘You’re crazy – take the medication.’

Guiseppi’s life is unbearable. My low self-esteem obliterates my feelings in any loving heterosexual relationship which I really long for. I can’t function. I can’t work. My peers are uncomfortable with me and unpleasant to me.

Marie is in her own world which alienates her from the reader and her peers and probably her family. It’s a curious narrative which leaves you wondering where Maria ended up.

For all the madness, the sense of lost dreams, the feeling of dependence, there is deep and compelling courage to keep going. What these 10 people live with is an undeniable difficulty with a brain/mind in freefall which creates seemingly insurmountable obstacles, and yet, they keep getting out of bed and getting through the day and having the courage to tell their stories. John is optimistic and looks on his schizophrenia as a source of growth rather than as something I have to manage. There can always be growth out of trauma.

The mental health world is full of competing narratives, and it is important to hear from them all. This book offers the clinical perspectives of a psychiatrist and a psychologist which take us through the symptoms and treatments they offer a person and their families. The notion of insight or loss of insight is often mentioned. And we see this evident in some of the stories in this book from those living with schizophrenia. Though the concept of insight is a contentious issue, with consumer activists saying having insight is simply saying what clinicians and families want to hear. But I know there have been times when I have lost the capacity to see how my thoughts and actions haven’t aligned with the wider world.

We see the mentally ill in disproportionate numbers in the prison population, and the challenges First Nations people endure. Michael Wright, a Yungu man and social worker and academic, challenges conventional western Euro-centric clinical ideas by saying Aboriginal people who may be hearing voices or seeing hallucinations, should engage Aboriginal healers such as Elders who are able to provide a cultural interpretation of this experience.

Sister Brigid Arthur who works with refugees is defiant, declaring with any sort of advocacy – particularly if it’s going against some powers in society – you have to be prepared to be unpopular. We Sisters have got nothing to lose by being unpopular, so we can speak out. She highlights the damage being done to asylum seekers and their fragile mental health by inhumane politics. And wants us all to be better global citizens.

Professor Alan Rosen, and Professor Maxwell Bennett, give us a manifesto for more inclusive, wrap around services, and a breakdown of the massive schizophrenia PR disaster of the Bondi Junction stabbings by Joel Caucchi who had a schizophrenia diagnosis. Jenny Burger highlights the gains made in making families included and visible in the treatment plans for their family members; to have consumers, carers and clinicians working together. To change the bloody system. And succeed. And the Ken Alexander’s wisdom in his Fourteen Principles, which are still as relevant to today as they were when first devised by Ken, are lessons in going from passive minding to active caring. And we learn about SANE diving into the modern world by providing online care for people with targeted and effective digital services.

We learn about The Clubhouse – a Community Psychosocial Rehabilitation programme which seeks to empower its members by encouraging them to actively take part in running the Clubhouses programmes to give them a pathway towards employment. And then we learn about First Step and the work they do to provide wrap around care for their clients. First Step is a not-for-profit addiction, mental health and legal services hub in St Kilda, Melbourne.

It provides a uniquely multi-disciplinary team of GPs, psychologists, nurse practitioners, lawyers, mental health nurses, care coordinators and counsellors along with an outpatient programme ResetLife. It is free. If you’ve got a compassionate doctor, a compassionate lawyer, a compassionate mental health nurse and a compassionate care coordinator who talk to each other all the time, you have what Professor Alan Rosen calls a village, a caring community where our goal is not to treat people and fix their problems. Our goal is to empower them and build their natural resilience.

Another shining light in the darkness of the mental health world is Heidi Everett who challenges us to rethink old assumptions about schizophrenia. Her brainchild, Schizy Inc, is a disability led organisation which is this whole massive year-round programme with a performing arts collective and a writers’ collective. Schizy Inc gives people who join, pride, identity, culture. Heidi challenges us to think about the notion of helping someone with a mental illness.

It’s really important that we start to reframe the word ‘help’ because people with schizophrenia and complex trauma don’t need help to survive. When you ask somebody if they need help without them first asking you, you’re assuming that this person doesn’t have the capacity to help themselves. People with schizophrenia and complex mental health are survivors. ‘Help’ is dragging somebody up whereas support is coming from underneath. Schizy is about building relationships with local arts organisations, communities and venues. We advocate access and inclusion around complex mental health and neurodivergence in a way the mental health system cannot. Schizy Inc builds the kind of spaces that make you proud to have survived your past. You deserve respect for your existence.

At first, I was concerned the carer and lived experience interviews were from a different era, to be reading about Larundel and Mont Park and old support services. But we need to know this history to show where we have come from and that much of what these people faced 20 or 30 years ago, sadly is still current. Not much has changed for families or the mad. And this is the tragedy. Has talking of now closed hospitals, old medications, old paradigms, dated the book? Made it irrelevant? Sadly no, because much of what is talked about in the book are still issues today: homelessness, prison, medication side-effects, lack of wrap around services, the need to include carers, the stigma still plaguing schizophrenia, the existential pain schizophrenia causes. Reading this is salutary. But also seeing the light shone by organisations like First Step and Schizy Inc and Clubhouses gives heart that good things can and are happening in the mental health world.

Margie shares her vision for the way forward where families become allies and not enemies. She talks about the need for collaboration, engagement, problem solving and empowerment, the need and benefits of supported housing, the proven efficacy of the Clubhouse model and the benefits offered by the Haven Foundation. And Margie reminds us that schizophrenia sits at the bottom of the lists of mental illnesses and generates fear, while other conditions garner public attention and support. Margie writes, We have given people with schizophrenia a voice. We have spoken to their carers. We have invited a wide range of men and women working in the field to speak their minds. This book reveals what it is like to live with schizophrenia.

Even after a Royal Commission in Victoria, which highlighted the appalling inadequacies of the mental health system; the same problems faced by the same people. Carers ignored, people needing care not getting it, clinicians holding power. We can only go forward by acknowledging and seeing the past. Living with Schizophrenia is a multifaceted, multidimensional book offering a comprehensive investigation into schizophrenia, the abandoned illness, which still perplexes those who live with it and those who care for and treat people living with it. By opening the conversation, hopefully it will open people’s minds and reduce the stigma and increase the supports needed to allow people to live less fraught and more hopeful lives. A book like this would have given me more hope when I first encountered schizophrenia; to see a shining light on a hill which would have given me more optimism while living with a beast I needed to tame. Congratulations Margie and Mary on your dedication in bringing this informative and important book into being. I am very happy to officially launch Living with Schizophrenia.

Monash University Publishing is delighted to see several of our authors featured at this year’s Brisbane Writers Festival, taking place 9–12 October 2025 at the Brisbane Powerhouse.

Lauren Samuelsson (A Matter of Taste), Tony Wellington (Freak Out, Vinyl Dreams and Mixtapes and MTV), Richard King (Here Be Monsters and Brave New Wild), and Bryan Horrigan (Corporate Social Responsibility in an Age of Existential Threats) will all be appearing across the festival program.

Together, their works span music, politics, culture, food and pressing debates about democracy and the environment – reflecting the breadth and ambition of Monash University Publishing’s list.

If you are in Brisbane, be sure to catch them in conversation and discussion throughout the festival.

You can find the full program here.

It is with great sadness that we at the Press pay tribute to the late Race Mathews (27 March 1935 – 5 May 2025), an MP, an academic and an author of great wisdom, interest and generosity.

Race began his career in the 1950s as a speech therapist in rural schools in Victoria, then graduated from degrees at Monash University, Melbourne University and the University of Divinity.

In 1960 he was elected Secretary of the Australian Fabian Society, joined the Australian Labor Party and became Principal Private Secretary to Gough Whitlam. He developed policies on education, health, gun control and more, was Minister for Police and Emergency Services and Minister for the Arts, and developed the inaugural Spoleto International Festival of the Arts and the Melbourne Writers Festival.

While in parliament in the early 1990s, Mathews was part-time visiting fellow in the Public Sector Management Institute at Monash University. After leaving parliament he became senior research fellow in the Institute, then in the Graduate School of Government at Monash University, and a Senior Research Fellow in the International Centre for Management in Government at Monash.

The Co-operative Movement was one of Race’s passions, and in 2017 our press published his book Of Labour and Liberty: Distributism in Victoria, 1891–1966.

The author of many books, Race’s biography Race Mathews: A Life in Politics – begun by Race, then completed by his wife Iola in 2024, was launched by Monash University Publishing to acclaim.

Race was an avid reader, a collector of science-fiction books and a lover of classic movies. As Race’s good friend, the Hon Gareth Evans AC KC, said ‘If only we had more people in political and public life like Race Mathews: compassionate, hugely competent, intellectually and culturally curious, much more passionately committed to good policy than personal or factional political advantage, and indefatigable.’

Race will be sorely missed by us all, and we pass on our sorrow to Iola and family.

Read the Victorian Premier’s media statement here.

Taking to the Field, a groundbreaking history of women in Australian science by University of Wollongong historian and Monash University Publishing author Jane Carey, has been awarded the 2025 Ernest Scott Prize for History.

Presented annually by the University of Melbourne, the prize recognises the most distinguished contribution to the history of Australia or New Zealand, or the history of colonisation. Dr Carey’s book challenges long-held assumptions about women’s place in scientific history and reshapes our understanding of the foundations of Australian science itself.

“I am deeply honoured that Taking to the Field has been awarded the 2025 Ernest Scott Prize,” said Dr Carey. “At a time when the humanities in general and history in particular seem to be under siege, having awards such as this that support historical scholarship on Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, and histories of colonialism, has never been more vital.”

In a meticulously researched and wide-ranging account, Carey traces the long and often obscured history of Australian women’s involvement in science, dating back to the 1830s. From amateur botanists and natural historians to participants in scientific reform movements such as eugenics, and later, to professional scientists, Carey uncovers a rich and complex legacy. Her interviews and surveys with more than 300 women science graduates reveal both the depth of women’s contributions and the enduring structural barriers they faced — including limited employment opportunities and systemic discrimination, particularly after World War II.

When molecular biologist Elizabeth Blackburn became the first Australian woman to win a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2009, she was celebrated as a trailblazer. Yet, as Taking to the Field reveals, Blackburn was part of a much longer lineage of women whose contributions were essential to the development of Australian science — even if they were largely overlooked in mainstream histories.

“This book is not simply a celebratory recovery of forgotten pioneers,” said Carey. “The impact of Western science has not been uniformly positive and women were certainly associated with some of its darker episodes. Holding these two things in productive tension provides, I hope, greater understanding and a firmer foundation for more women in science into the future.”

Dr Carey also acknowledged the support of Monash University Publishing and the women who shared their stories. “Many thanks to my publisher, Monash University Publishing, for all their support and the outstanding work they do in supporting scholarly publishing generally. To the more than 300 women who shared their experiences of studying and working in science with me, most of whom are no longer with us, I am profoundly grateful.”

Taking to the Field is a significant contribution not only to the history of science and women’s history, but also to broader understandings of colonialism and social change in Australia. It affirms the vital role of historical scholarship in shaping a more inclusive and accurate national story.

Maggie Nelson opens her luminous work of prose-poetry Bluets with the following provocation: ‘Suppose I were to say I had fallen in love with a color’. Blue, for Nelson, is the colour that ravishes her senses, signifying the beginning of love and the end of life. Goethe writes: ‘We love to contemplate blue, not because it advances us, but because it draws us after it’.

Verge 2025 is looking for new writing that responds in some way to the colour blue.

Share with us poetry that alights the senses with blue; narratives infused with shades of cobalt, indigo and cerulean; any and all writing tinged with this most mysterious and evocative colour.

Guidelines:

We welcome submissions from all writers in Australia. We seek short fiction, poetry, creative non-fiction, experimental or hybrid works, and artworks. Artworks will be published in greyscale.

You may submit up to three works in one document. Fiction and non-fiction should be no more than 3,000 words in length. There is no line limit for poetry, and submission in A5 document size is encouraged. Please only submit previously unpublished work. Simultaneous submissions will be considered but please let us know if your work has been accepted elsewhere.

There will be prize money on offer for best overall and best student submission, with the amount to be confirmed closer to the submission closure date. All contributors will receive one copy of the print book. The book will also be published online.

Submissions close 9 February 2025,11:59 pm AEDT.

Please send your submission to verge.monash@gmail.com. In your email, please include your name, contact details, and a brief author bio (no more than 50 words).

If you are a student at Monash University, please indicate in your email whether you are undergraduate or postgraduate.

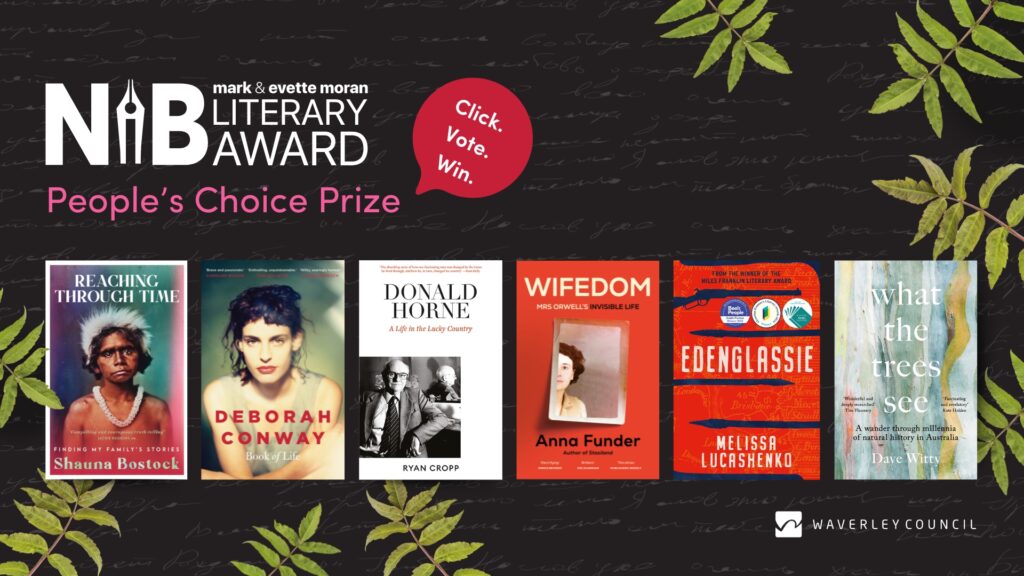

Dave Witty’s What the Trees See has been shortlisted for the The Mark and Evett Moran NIB Awards 2024! VOTE HERE